Divisible by Thirteen

May 28, 2025 pm31 10:01 pm

Just a little math puzzle.

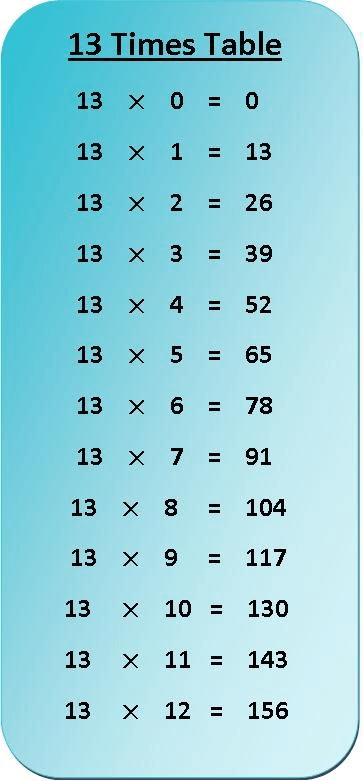

86 is not divisible by 13. But turn the 8 into a 2, and now it is (26).

62 is not divisible by 13. But change the 2 to a 5, and now it is (65).

Is every 2-digit number divisible by 13, or a number that can be made divisible by 13 by changing one digit?

If yes – explain why (and the explanation should be good enough to convince a high school freshman).

If no – show a 2-digit number that is not divisible by 13 and cannot be made divisible by 13 by changing one digit.

5 Comments

leave one →

So it seems like there are four examples: 44, 47, 84, and 87 — which would have been more work to figure out without the times table you provided :).

If we replace 13 by 12 then I think 51, 53, 55, 57, and 59 are the only examples (right?).

I haven’t thought too hard about it but if b is a base > 2 and s is a two-digit number base b, other than b and b + 1, is there always an example?

Arrange the numbers in a 9×10 grid (like a chessboard?)

Can 7 rooks attack every square? If they are non-attacking, how many squares in all will not be attacked?

12 corresponds to rooks that attack each other. Maybe look at (b,s) = 1.

Must 9 non-attacking rooks attack every square?

This is a nice way to think about it. Maybe (following your comment below) I would even say we should allow one-digit numbers (as two-digit numbers whose first digit is 0). Working through the details: if we’re in base b, then we have a b-by-b square. The multiples of (b + 1) are the diagonal of the square, and from every other square we can move to the diagonal by a rook’s move. If we consider the multiples of (b + k) for k > 1, the smallest one is 00 = 0 * (b + k), and the largest of them is definitely at most (b – 2) * (b + k) because (b – 1) * (b + k) > (b – 1) * (b + 1) = b^2 – 1, so (b – 1) * (b + k) has at least three digits. Thus there are at most (b – 2) + 1 good spots on the b-by-b square; so some row doesn’t have a good spot, and some column also doesn’t, and so the intersection of that row and column is what we want.

Furthermore, if b and b + k (equivalently, b and k) are relatively prime, then these rooks will all be in different rows and different columns, so the unattacked cells will form a nice square grid (spread out in the bigger square, not necessarily regularly). When they’re not relatively prime, some of the rooks will end up in the same columns, so we’ll end up with a rectangle with extra columns instead of a square; definitely the gcd of b and k is relevant (I guess we can hit at most b/gcd(b, k) different columns?).

P.S. No post on the mayoral primary? You’re in the Bronx, that’s Cuomo country, right ;) ?

Should we consider 40 and 80? I think someone would need to specify whether to allow “change” to include “delete” – which way is more interesting?

Oh good point, I didn’t think about 0 at all! On reflection, I would vote that 40 shouldn’t count (because 00 = 0 is a multiple of 13), which I suppose would make my original answer correct but only by accident :-).