George Thomas: An Old Dead White Guy who could use a Statue

(This is not my usual entry – it’s a bit about a little-known Civil War General – if it’s not your thing, no worries – I’ll be back with regular writing tomorrow. – jd)

I’m all for tearing down confederate statues. I’m all for taking their names off of buildings and bridges and schools? Who the hell put their names on schools? Slaveholders, racists, subject them to scrutiny, and I’m good with the same treatment if that’s where the discussion goes. And I’m cool with replacing them with abolitionists and revolutionaries, but I’m much cooler replacing them with abstract themes and groups of people – statues of enslaved people freeing themselves, workers on strike, native people refusing to vacate their land. Or how about Emancipation High School, Liberation Federal Building?

History is not a series of names of old famous dead white men, or a series of names of old famous people. Especially in the last century, but I claim further, history is made when the people in the middle or the people at the bottom, nameless, faceless, forgotten, when the majority have had enough, or when the masses move to change things. Wars are won by infantry, not generals. We remember the sweet words of the leaders, but nothing happens with just words – movements of people make change, make history.

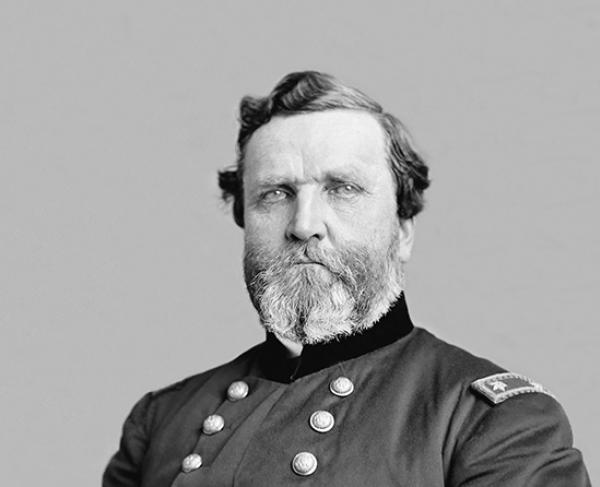

But, in a contrary thought, I want to talk about a neglected dead old white guy – George Thomas. Let me make the case – if there’s an old dead white guy we should build even one monument to, it should be him.

Not making the case – Thomas’ early career

George Thomas was from Virginia. His family owned other people. He went to West Point. He fought in the Seminole War in Florida, where the US tried to forcibly remove native people from Florida. He fought in the war against Mexico (and in fact served alongside of Braxton Bragg, whose name currently stains a fort in North Carolina) as the US annexed vast parts of northern Mexico. He returned to duty in Florida, and then trained officers at West Point, where he was friends with Robert E. Lee, where Lee put him in charge of cavalry and artillery training.

I haven’t made much of a case yet, have I?

An aside, about this man who seems on course to be a despicable footnote in history, his specialty was artillery, and tactics, and he was good, and methodical. He jury-rigged artillery with ropes, to bring guns into line of sight, fire, and pull them immediately out of line of fire in Mexico. There are battles that would have gone the other way without him. At West Point he taught artillery. He was methodical. On riding, he would not allow cadets to gallop when they were supposed to ride at a trot, and he was nicknamed “Old Slow Trot Thomas.” He had a reputation for being deliberate.

Ok, that doesn’t help the case either. Let’s push on.

Not as bad as his peers – Not much of a case

So it’s 1861. The slaveholders’ begin their rebellion. They capture control of one southern state after another, and the allegiance of one army officer from the south after another. There’s one high-ranking officer left, and one state: Robert E Lee, and Virginia. On April 4 a Virginia convention votes to remain in the United States. Another vote, April 17, and Virginia joined the slaveholder rebellion. And on April 20 Robert E Lee resigned from the United States Army.

On April 21, 1861 George Thomas was the highest ranking southern officer to remain in the United States Army. And he remained so, until the end of the Civil War. But that’s like being the highest ranking member of an organized crime family not to have murdered someone. Being less bad is not really a claim to fame.

A key victory – OK, he’s competent

The Civil War began. We learn about it as a two-front affair: Virginia/Maryland (from Richmond to DC and back), and the Mississippi River (Shiloh, New Orleans, Vicksburg). But there’s another active theater: Kentucky and Tennessee. The former stays in the Union, the latter secedes, but both are divided, and there is active fighting from the beginning of the war. Fighting in the western part of the states eventually led to Shiloh. But we are interested in the moment in the east. There was rich farmland, with provisions that both armies needed. And the east was home to concentrations of Unionists, including the region of Tennessee where Lincoln’s family was from; protecting Unionists was a priority of Lincoln’s.

Through 1861 the United States suffered a series of military defeats. There was a diplomatic crisis with England; the United States backed down. 1862 opened and the confederates tried to invade Kentucky. The first major US victory of the war? Mill Springs, where the confederates were beaten, and driven out of their camp, and Kentucky was protected. The commander? George Thomas. Knock on Thomas? When soldiers took good initiative, it was the field commanders and not Thomas himself who gave the orders. Hmm, trusts his subordinates? How’s that bad? (Aftermath – two more victories, these by Grant, further west in Kentucky). So first major victory – Thomas. But we’d already established he was a competent officer. Does that merit a statue?

What the Hell is Tullahoma?

I’m going to introduce this next story twice, and then not tell it today.

I remember learning about the Revolutionary War in high school. The story jumped around – I remember acutely feeling the lack of narrative thread. The campaigns were disjointed, separate stories, except for Trenton and the Delaware. But one story worked well for me – at Yorktown as the forces came onto the field, and the French arrived, Cornwallis assessed the situation and surrendered. Very satisfying story, though perhaps not very accurate. But where is the equivalent in the Civil War? There is none, except…

DIfferent question. July 3, 4, 1863. Huge days for the Union. Gettysburg victory. Fall of Vicksburg. But something’s missing. In Gettysburg, a raiding party in force accidentally engaged in a 3 day losing battle – 8,000 dead on both sides, but the invasion of Pennsylvania was defeated. Lee returned to Virginia, and not much territory changed hands. Vicksburg? Predicated on the seizure of New Orleans over a year earlier. A month and a half siege, after frontal assaults failed. The result was inevitable, and occurred after almost 1000 US troops were killed (and maybe three times that of confederate soldiers).

But July 3, 1863 was also the culmination of the Tullahoma Campaign. What? You’ve never heard about the largest territorial advance during the entire Civil War? Rosecrans was in charge. But Thomas was responsible for the perfect planning, practice, preparation, and execution. Traitor Braxton Bragg was routed. Realizing his position untenable, he retreated, yielding a thousand square miles, surrendering control of all of middle Tennessee, while barely firing a shot. 83 US soldiers were killed, and maybe 200 rebels. Rosecrans complained bitterly to Secretary of War Stanton: “I beg you…do not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.”

I think I want to make some maps and try to tell the story of Tullahoma another time. But here’s a link if you are curious. But the author of the greatest forgotten union victory of the war – worth a statue? Maybe. But probably not worth fussing over.

The Original Rock

Having been driven back to Georgia after Tullahoma, Bragg tried to regain the offensive and retake Chattanooga. He engaged Rosecrans in September, near Chicakamauga Creek. Rosecrans moved the wrong unit in the wrong direction, opened a gap in the line, and a rout began. Rosecrans and much of the Union army retreated north in disorder. George Thomas reorganized the remaining defenders, and held off Bragg for long enough to allow an orderly retreat. Anyway, for calm under fire, methodical organization, executive control of the battlefield, future president Garfield labeled him “The Rock of Chickamauga.” Bravery in a loss? Prevented a rout? Let’s keep that in the history books – not sure it makes the case for a statue.

After the retreat, the US forces were besieged in Chattanooga. Grant took over. After two days of success, they planned to take the heights at the east of town, called Missionary Ridge. Sherman, Grant’s bud, was going to take it from the north. he assigned Thomas to charge the center, right up to the base of the steep slope, and stop. Sherman fights a vicious battle, without success. But Thomas troops take the base of the ridge, and they take the initiative: they scale it, red white and blue colors, with blue coats in “V” shaped wedges behind, moving vertically. Grant blows a gasket. First flag up is the drummer boy from a Wisconsin regiment – it’s General MacArthur’s father. Thomas’s troops rout Bragg’s, and the battle is won. All good stuff – and it’s adding up. But outstanding? Not sure the case has been made yet.

Nashville where the case gets strong

After Chattanooga the US Army pushed south. Grant went back to Virginia. Sherman took command for the “March to the Sea.” And Thomas was left to defend the remaining rebel army, Hood’s Army of Tennessee. Hood pivoted west, and then after resting in Alabama, moved north for another invasion of Tennessee. His fantasy was a drive north though Nashville, onward to Kentucky, then Ohio, then east to meet up with Lee. Reality was a horrific series of charges, Pickett had nothing on the brutality, south of Nashville, against one of Thomas’ commanders, and then a march to Nashville, where Thomas was ready.

There is a common knock on Civil War commanders, that they won a battle, but did not finish off their opponent. It’s kind of unfair – the retreat is easier than the chase; defense is easier than offense. And in a bit of unfairness, southern Generals get a pass on this, even though their record was no better. When did Lee pursue a defeated opponent? Actually, during the entire war, no general followed up a victory by shattering and finishing their opponent. Except for George Thomas, at Nashville. Hood entered Tennessee with 38,000 soldiers, and left with 15,000. Many of his top officers were killed – with war criminal Nathan Bedford Forrest, who was sent away before the rout, a notable exception. The “Army of Tennessee” surrendered a few months later in North Carolina, without seeing another major engagement.

Did I mention anything about Thomas’ views on race? I think he was a racist. I think he thought Blacks were inferior. Nashville changed him. Ordered to incorporate freedmen into his army, he did. There were separate “colored” units, but they trained alongside white units, with the same training. They were seasoned by going out on sorties, side-by-side with white units. And Thomas noted their performance. Our sensibilities might be offended that he was surprised that Blacks fought as well as whites, but surprised or not, he reported honestly. And then after Nashville, among the dead he saw Black soldiers who clearly had held their positions longer, and he noted their greater bravery…

We have a history teacher in my school who is great on this sort of detail. Did he know who Thomas was? Of course – and he rattled off a half dozen notable details. I had been reading, and struggling to learn the little I knew. But this guy had the best stories, including one that was new to me: After Nashville, confronted with the task of burial, he was asked about separate plots for each state: “No, no, no. Mix them up. Mix them up. I am tired of states-rights” – This is political evolution.

I don’t know. Is that enough? Everything already mentioned, plus the most smashing victory of the war, plus positive evolution in his thinking on race, plus a political evolution? We are getting close.

Post-War

Thomas was a military commander after the Civil War, with responsibility in Tennessee and Kentucky, and sometimes other states. He carried out reconstruction faithfully, and aggressively pursued the Klan. He opposed attempts to recast the war as anything but treason, and was a defender of the freedmen. Offered a political appointment, he instead took a military command in California, where he died of a stroke.

Afterwards

At the end of the war Thomas was in the pantheon with Sherman, Grant, and perhaps Phillip Sheridan. These were the greatest generals on the winning side. Sherman proposed that statues of Grant and Thomas be erected side by side. Thomas shows up in a silly wikipedia list – the only North American commander never to lose a battle (don’t know if he really NEVER lost, or if no one else should qualify – it’s wikipedia). It is true that Thomas burned his papers, and did not publish memoirs. And while he was friendly with Sherman, him and Grant, nah. Among other things, Grant was not happy about Missionary Ridge, or how long Thomas took to prepare for Nashville (events showed Thomas was right) or with Rosecrans for Tullahoma (events also bore out Rosecrans’ and Thomas’ decisions).

Thomas was shunned by his Virginia family. He is buried in Troy, NY, with his wife, a Troy native.

Why is he forgotten?

Some say that as a Virginian against the rebellion, his legacy has no natural supporters.

Some say that Grant downplayed his contributions.

Some say that the self-promoting veterans, with their memoirs, outshone Thomas.

Some say that he just fought in the wrong battles. Mill Springs was too early. Nashville was too late. Tullahoma was not dramatic enough, and eclipsed by Gettysburg and Vicksburg.

But I don’t buy any of that. I think it’s political. A southern leader against secession. A man from a slaveholding family, seeing worth in Black lives, even superiority, actively applying reconstruction, standing up for freedmen, battling the Klan. A southerner changing his mind, on politics, on race. When the fake version of the Civil War, “The Lost Cause” was ascendant – George Thomas’ very existence revealed its falseness. He was inconvenient. And conveniently forgotten.

His evolution on using Black soldiers is striking:

The Confederates regard them as property. Therefore the Government can with propriety seize them as property and use them to assist in putting down the Rebellion. But if we have the right to use the property of our enemies, we share also the right to use them as we would all the individuals of any other civilized nation who may choose to volunteer as soldiers in our Army. I moreover think that in the sudden transition from slavery to freedom it is perhaps better for the negro to become a soldier, and be gradually taught to depend on himself for support, than to be thrown upon the cold charities of the world without sympathy or assistance – 1863

Thomas’ early biographer:

“When the enlistment of the manumitted slaves was ordered by the National authorities no department commander performed his duty in giving efficiency to colored regiments more loyally than General Thomas. He gave advice and encouragement to the officers who were engaged in organizing and commanding negro troops in his department. And when these troops exhibited their proficiency in the manual of arms and drill, he was often among the delighted spectators.”

And then the record – no fake assignments, no hopeless charges, this was not Glory – at Nashville Black AND White units together harassed Hood’s right, to allow the balance of Thomas’ army to wheel and smash the left.

And then after the war….

[T]he greatest efforts made by the defeated insurgents since the close of the war have been to promulgate the idea that the cause of liberty, justice, humanity, equality, and all the calendar of the virtues of freedom, suffered violence and wrong when the effort for southern independence failed. This is, of course, intended as a species of political cant, whereby the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains; a species of self-forgiveness amazing in its effrontery, when it is considered that life and property—justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations, through the magnanimity of the government and people—was not exacted from them. – George Thomas

And there’s his record of actively countering the Klan.

So yeah, I’d put up a statue. No, it’s not the top of the list. But next time we strip Braxton Bragg’s name, or John Bell Hood’s, think about using Thomas to replace them. Or when we topple one of those despicable statues of war criminal Nathan Bedford Forrest, consider George Thomas as a replacement.

I’m driving upstate, one day soon. And I will hit a trifecta: Harriet Tubman (Auburn, near Syracuse), John Brown (North Elba, near Lake Placid), and George Thomas (Troy). Seems fitting.